Both in the Ukrainian and pandemic crises, mass-media seem to apply the same approach to drive public opinion toward a virtually unanimous consensus. Media blatantly flaunt radical dissidents on major TV and newspapers to systematically pillory them. Some of them play the game unintentionally; others might even be conscious accomplices.

It works as follows: mainstream media offer a large audience to the supporters of the most extreme positions and to any kind of morons to be ridiculed. They also provide a poorly educated audience to baffling highbrows who are unable or reluctant to communicate in a short and straight way. Thus, they too are publicly mocked.

More moderate dissenters or nonconformists are not given any chance to argue the mainstream messages. The strategy aims at deliberately polarizing the positions knowing that one of them is largely superior. Strategists pinpoint a weak enemy to create the opportunity to repeat once and again the mainstream narrative.

Attacking and belittling the dissenters let undecided citizens fear marginalization and urges apathetic people to go with the crowd. The other citizens, who already share governments and mainstream media’s views, stuck in their opinions even more confidently.

If in the case of pandemic, it was necessary and relatively safe to create a widespread agreement, the same strategy turns very dangerous when applied to rearming and to a possible direct involvement in war.

Thus, the link between the health crisis’ approach to communication and to the building of public opinion in the current geopolitical and military situation is worth being carefully handled.

It is unlikely that an occurrence like the pandemic, which so deeply affected people’s life and required so much mass information to cope with, did not change the socio-political milieu.

Governments urged – and in some cases forced – even the most reluctant citizens to vaccinate and imposed strict rules in a condition of scientific uncertainty. To implement mass vaccination, it was necessary to create the most extensive consensus. This task has been completed by applying advanced communication tools which likely have been improved during the health crisis. In the last two years, governments’ communication strategists have collected a huge experience in the building of an unchallenged public opinion.

Democratic governments in many cases handed over to scientific institutions and even to the military some pivotal decisions about pandemic. It might be sensible to trust institutions in a condition of collective risk but the more you move forward on this path, the more difficult will be to come back to free information.

During the last two years, some top intellectuals spread doubts about quasi-mandatory vaccination in most EU countries. Though we may agree about principles they uttered, during the pandemic and for a short while it was appropriate to hold the full implementation of some constitutional principles. By the way, the against-the-stream top intellectuals have been instrumentalized by the propaganda along the previously reported lines; namely, TV anchorpeople and journalists exhibited those refined thinkers and their ideas to prompt sarcasm of uneducated audiences. Regrettably, most of the times with their consent.

Is it plausible to think that the communication strategies, elaborated to create a mass consensus during the pandemic, are now applied to create a large support to the war and to rearming?

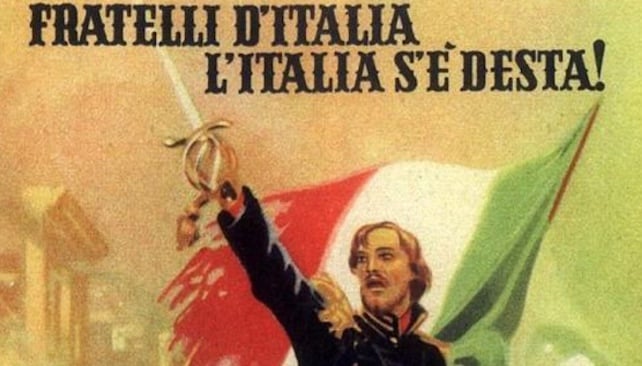

Since more than two years, Italian government relies on a majority of almost 90% of MPs and is led by a representative of the international community who never ran for office. We may assume that this approach was appropriate to cope with the pandemic crisis. Is it still when war, rearming and geopolitics are at stake? What will be the long-term effects of the holdup of some substantial constitutional procedures on the establishment of a possible regime?